My research for my grandparents

a simplified explanation of my work

The color of the more distant galaxies

We still do not know exactly how galaxies form and evolve. There are a lot of physical processes taking place over very long times (billions of years), that it is not possible to simply observe them.

We can investigate it by observing galaxies at different distances because, given that the Universe is expanding, and that the light travels at a well-defined fixed speed, looking further means also looking back in time.

This concept can be well understood with the concept of "light year". This unit, even if it has the word "year" in the name, is used to measure distances. In particular, if we observe something at, for example, 100 light years, we are observing it as it was 100 years ago, because the light that is travelling from that object takes exactly 100 years to reach us.

It is also true for nearby objects: when you look at the Sun, you are observing it as it was 8 minutes ago!

Thanks to the most advanced telescopes, we can now observe galaxies more distant than 12 billions of light years, and thus observe the very young ages of the Universe.

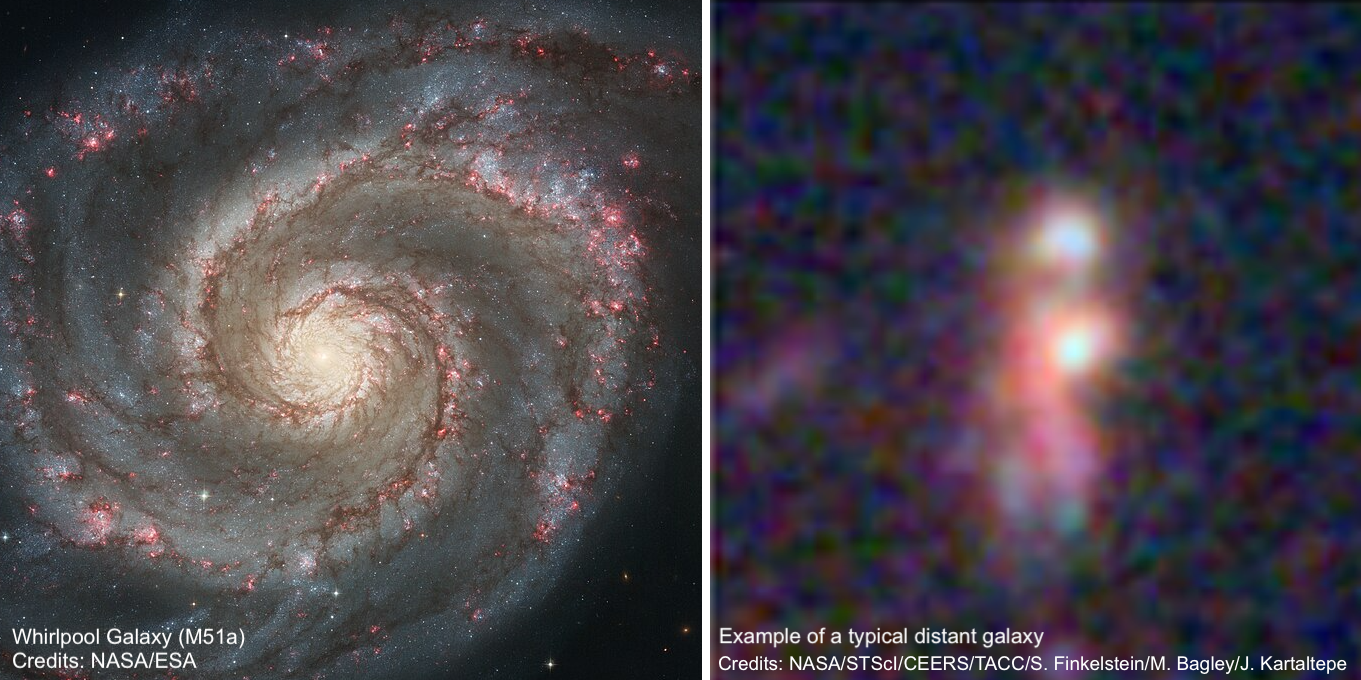

What we observe is that those galaxies appear very different than those we observe today (see figure on the right). We know that they have more gas and are forming a lot of stars in dedicated regions, that appear in our images as intense light blobs.

It is one of our primary interests the study of these regions, because we can learn a lot about the mechanisms that drive the galaxy evolution.

What we observe is that those galaxies appear very different than those we observe today (see figure on the right). We know that they have more gas and are forming a lot of stars in dedicated regions, that appear in our images as intense light blobs.

It is one of our primary interests the study of these regions, because we can learn a lot about the mechanisms that drive the galaxy evolution.

In particular, we are interested in the kind of stars that lives in these regions. Are they young or old? Are they hot or cold? Are they immersed in the dust or not? Do they live individually or are they linked in couples?

To solve these questions I study their colors. Given that they are very far objects, we cannot observe every individual star, but just the total light emitted by their population. Luckily, we are able to recognize the physical properties of those stars only observing their colors.

For example, stars appear red if they are old, metal-rich, and immersed in the dust, while they appear blue if they are young and massive. In some case, we can also know how many stars were big and massive and how many small and red at the beginning, and reconstruct their evolution.

What I discovered is that those bright regions evolve differently than the entire galaxy they are hosted by, and that they are the forge where new stars are created. I also discovered some very special region that is "too blue": we are not able to explain their color. A usually happens in Astrophysics, and in science in general, this makes these objects extremely interesting.

In the next years, I will focus on their characterization, and I will try to understand their origin.

Gravitational lensing: the more massive, the more the deflection

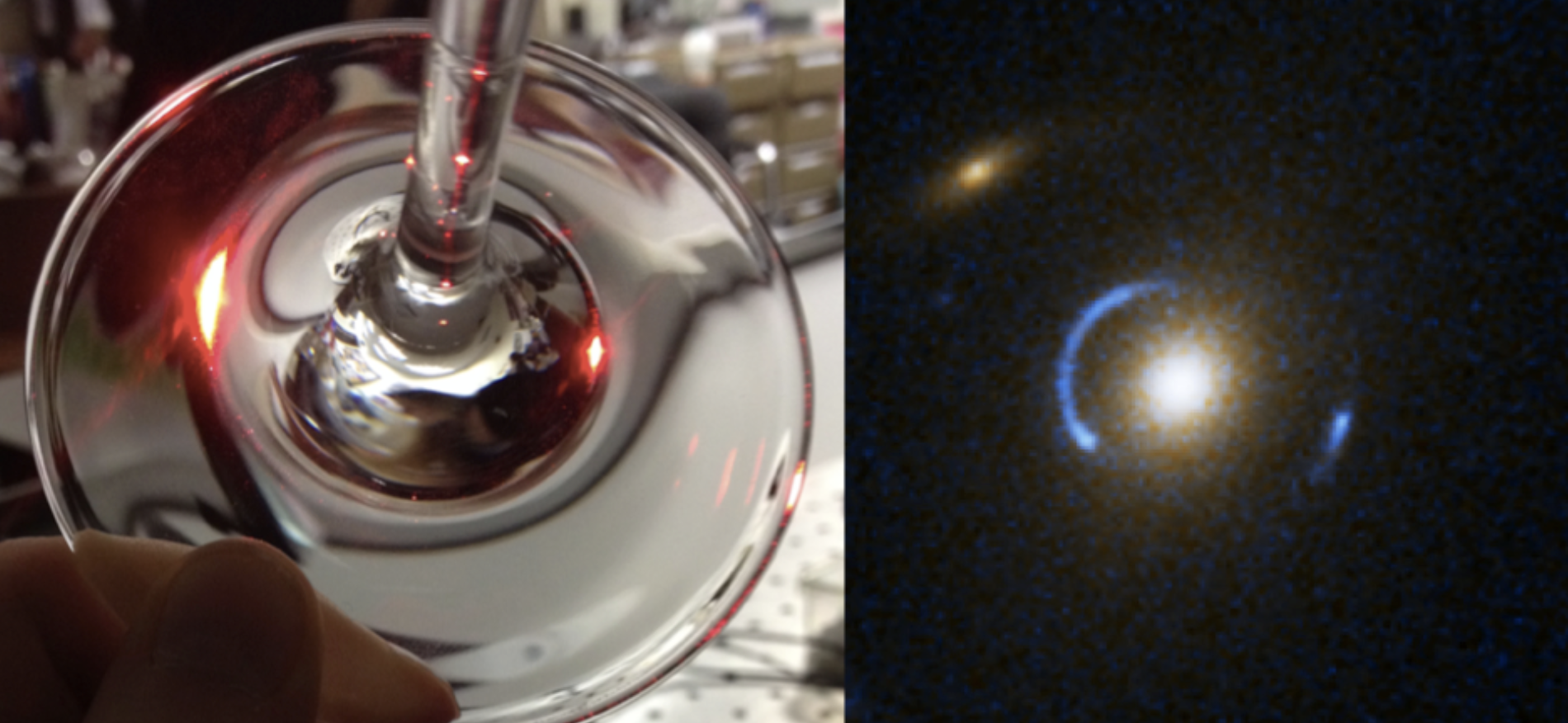

Imagine the Universe as the largest magnifying glass. As you can see in the left of the figure (from Samantha Scibelli's site) for special glass geometries you can see multiple, distorted images of a red light in the background. It happens the same with the Universe: what distorts the light path is, in this case, the mass of some massive objects. In the figure on the right, you can see a galaxy, in yellow, that bends the light emitted from a background source, in blue, that results in an elongated arc and another separated image.

And why is there also a picture of the sea? The light lines we see, are called caustics. They are originated by the irregular surface of the water, that concentrates the Sun rays in particular locations. Following the same definition, there are also caustics in Gravitational Lensing!

Imagine the Universe as the largest magnifying glass. As you can see in the left of the figure (from Samantha Scibelli's site) for special glass geometries you can see multiple, distorted images of a red light in the background. It happens the same with the Universe: what distorts the light path is, in this case, the mass of some massive objects. In the figure on the right, you can see a galaxy, in yellow, that bends the light emitted from a background source, in blue, that results in an elongated arc and another separated image.

And why is there also a picture of the sea? The light lines we see, are called caustics. They are originated by the irregular surface of the water, that concentrates the Sun rays in particular locations. Following the same definition, there are also caustics in Gravitational Lensing!